At the beginning of the project, driven by curiosity about my schizophrenic grandmother and romanticized imaginations of her madness, I attempted to analyze her mental structure after her descent into madness and how she became that way. In the process of analyzing my grandmother, I discovered many similarities between us. Our lifelines seemed tightly intertwined. I never knew the rational version of her; my childhood was spent with her in her madness. I felt love, but I didn’t know where this love came from. In her, I saw myself, my mother, and the future of my relationship with my mother. All of this filled me with curiosity, compelling me to keep questioning.

Carrying these questions, I embarked on the project. However, as the analysis progressed, my questions gave rise to even more questions. While delving into my grandmother’s family history, these inquiries gradually evolved into a curiosity about myself—how my present self was formed, why my visual works take on their current form, and how, in my unconscious state, I was able to create such coherent and orderly series. This led me to explore my personal history. Over the course of more than a year of conversations, we indexed and analyzed my childhood, adolescence, and several critical stages that later triggered the collapse of my mental state. Through dialogues centered on my personal choices and my family of origin, my long-standing confusions were untangled into fine threads of clues, some of which gradually surfaced.

在项目的初始,抱着我精神分裂的外婆的好奇,抱着对她的癫狂的各种浪漫化的想象,试图分析癫狂后的她的精神架构和她如何变成这个样子,在分析外婆的过程中,我发现自己与外婆的诸多相似,我们的生命线好像紧紧地交织在一起,我与理智的她素不相识,我的童年与疯癫的她一同度过,我感受到爱,但却不知道这个爱从何而来,我在她身上看到我,看到我的妈妈,看到我与妈妈的未来,这一切让我充满好奇,想要不断的追问下去。

带着诸多疑问,我开始进入这个项目,但是随着分析的进行,我的疑问生长出了更多的疑问,在追问外婆的家族史的过程中,这些追问渐渐发展成对自己的好奇,对现在的自我是如何形成的、我的视觉作品为何呈现此种面貌,在我无意识的状态下,为何能形成如此连贯、有秩序的系列的好奇,展开了对自己个人史的探索。在长达一年多的会谈里,我们索引分析了我的童年、青少年以及后来引发我精神状态崩塌的几个重要阶段,通过围绕我自己的个人选择和我原生家庭的对话整理后,我对我自己长期的疑惑被梳理成一条一条细丝般的线索,有一些慢慢浮出了水面。

“Sumei” was the name of my maternal grandmother, born in 1928 and departed in 2010. Owing to a taciturn disposition among the senior members of my family, the details surrounding her remained elusive until the occasion of her cremation, revealing to me for the first time the veritable constituting her true name.

What prompts me to delve deeper into my grandmother’s life?

In the intersection of my life with my grandmother, I once felt a void in not knowing her lucid self. However, as I embarked on the extensive journey of exploring our family history since 2022, conducting interviews with those who knew her in clarity, tracing her footsteps, and discovering the fragments she left behind on this earth, I realized that conversing with her directly was unnecessary; I had already known her. Be it in her lucidity or madness, she wholeheartedly provided nurturing love and protection to our family.

I aspire to document the life of this woman, for within her, I see my past, my future—a flesh-and-blood human navigating the challenges and oppressions of society, wounded by her own sensitivity and resilience, resisting societal norms until her mental structure collapsed. She remained indomitable; her defiance leading to the fragmentation of her psyche. In that era, those who “survived” either chose to forget the past or to numb themselves, moving onto the next speculative game.

The documentation of this process holds significance not just for me or my family but, through a feminine perspective, delving into history unveils a narrative starkly different from grand historical accounts—a narrative more authentic, reflecting the depths of humanity.

I feel the need to revisit the life journey of this woman repeatedly, as these experiences provide me with more points of reference. Through these references, I gain a clearer understanding of my origins and potential destinations—a decision that rests solely with me, not dictated by male elders or partners.

Sumei’s lifeline:

https://www.lixinweicn.com/2025/02/timeline-of-su-meis-life/

“苏梅”是我外婆的名字,她出生于1928年,于2010年去世,因为家庭内的长辈们一直回避讲述她的事情,所以在她去世火化的时候,我才第一次得知她的真名是哪两个字。

是什么原因让我想要追问外婆的一生?

在我与外婆的人生相遇中,我曾认为没有认识过清醒时候的她,是一种缺失。但是在2022年开始做家庭史的漫长过程中,通过访谈对她清醒状态有记忆的人,搜寻她的痕迹,寻找她遗留在人间的碎片之后发现,原来不需要真正的与她交谈,我早已经认识她,无论是清醒的她还是疯癫的她,她都倾尽全力给予家庭爱的滋养和保护。

我会想要记录下这个女人的一生,在她的身上我能看到自己的过去,自己的未来,一个有血有肉的人类,怎么在这样艰难压抑的社会中被伤害,因为自己的敏感坚韧,与社会对抗,最后精神结构崩塌。她一直是不屈的,正因为她的不屈,才造成了自己精神分裂的后果,在那个时代“活下来”的其他的人,要么选择忘记过去,要么自我麻痹转身投入下一场投机博弈之中。

这个过程的记录不仅是对于我或者对于家人是有意义的,通过女性的视角,去回顾历史,能找到和在案的宏大历史叙事完全不同的东西。一种更真实的、更能反映人性的东西。

我认为我需要反复阅读这个女性的生命历程,这些事情能给我更多的参照,透过这些参照,我更清楚地知道我从哪里来,或许可以去向何方——我自己决定,不是男性长辈、伴侣帮着我做的决定。

The birth chart of Sumei : Acrylic, Mixed media on wall, 3*3(m)

《关于外婆星盘的研究》:墙上综合材料,3*3(米)

Sumei : Acrylic, pencil, charcoal, wall painting, 20*3(m)

《苏梅》:丙烯、铅笔,炭笔,墙面绘画,20*3(米)

Untitled(Portrait of Sumei) : capsules, wooden balls, dimensions variable

《无题(外婆的肖像)》Untitled (Portrait of Sumei):空胶囊,木球,尺寸可变

Waves,Soliloquy : video 14:02 , dimensions variable

《海,自言自语》:影像14:02 尺寸可变

Timeline of Su Mei’s Life

(1) Born on May 21, 1928, at midnight in Wenmingpu Town(In Chinese, it means “civilized town”.), Qiyang County, Yongzhou City, Hunan Province.

(2) 1930s-1940s – Both parents passed away.

(3) Around 1940 – She and her siblings were adopted by their aunt.

(4) 1946 – Married in Wenmingpu Town, Qiyang County, Yongzhou City, Hunan Province.

(5) 1947 – Gave birth to her first child, a daughter.

(6) Her eldest daughter passed away due to suffocation while she was inexperienced in childcare, leading to a tragic incident.

(7) 1948 – Gave birth to her second child, a son.

(8) 1949 – Gave birth to her third child, a daughter.

(9) 1950 – Husband enrolled at Guangxi University, prompting her to move to Guilin, Guangxi, with her son and daughter.

-Her younger brother joined the military academy, later sent to the first campaign of the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea.

-Her cousin was arrested for a mistaken slogan during the resistance in the the first campaign of the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea, leading to mental illness and labor reform.

(10) 1953 – Her daughter, afflicted with rickets, was taken back to Hunan Province at the age of 4 by her sister-in-law and later passed away under unclear circumstances.

(11) 1954 – After her husband’s graduation, they settled in Yan Shan, Guilin, with their son.

(12) 1956 – Gave birth to her fourth child, a daughter.

(13) 1958 – Relocated with her family to Nanning, residing at the Teaching Experimental Farm of the Guangxi College of Agriculture.

(14) 1959 – Gave birth to her fifth child, a daughter.

(15) 1961 – Gave birth to her sixth child, a daughter.

(16) 1962 – Gave birth to her seventh child, a son.

(17) 1962 – Underwent sterilization surgery.

(18) 1963 – Experienced postpartum depression, leading to self-talk and the initiation of tranquilizers under doctor’s guidance.

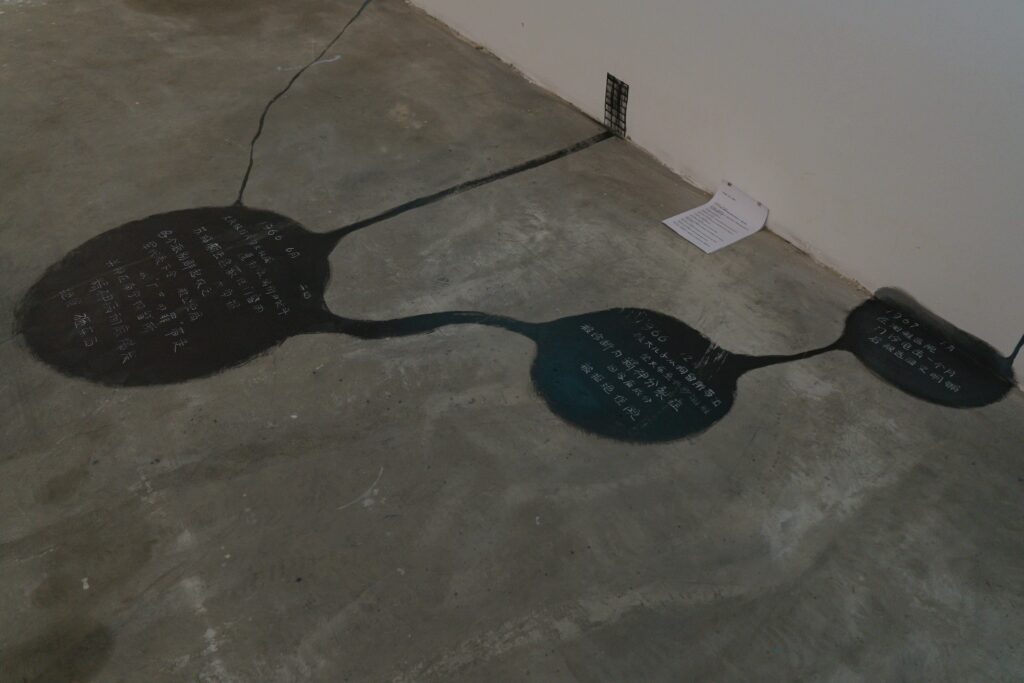

(19) June 1966 – The Cultural Revolution began, and her husband was denounced as a reactionary academic authority. Their home was ransacked, paraded through the streets, publicly criticized, and the door and windows of their residence plastered with big-character posters. Various factions rose against them, with the military representative issuing orders. Subsequently, She was taken away by the public security bureau on charges of “counterrevolution.” She was then detained in the Nanning detention center. Inside the detention center, his mental state deteriorated drastically, leading to hunger strikes and acts of vandalism.

(20) December 1966 – Her eldest son rescued her from detention and took her to Xiangya Hospital Psychiatric Department in Changsha City, Hunan, Province, diagnosed with schizophrenia, being denied hospital admission due to a background as a landlord.

(21) January 1967 – After a month of outpatient electroconvulsive therapy at Xiangya Hospital, her eldest son took her to recuperate at the home of her second brother in Wenmingpu Town, Qiyang County, Yangzhou City, Hunan province (She is only allowed to return to the place of her birth.).

(22) August 1968 – Her eldest son accompanied by her two sisters and one brother, brought Su Mei back from their home in Hunan to Nanning, where her condition improved.

(23) End of 1968 – Experienced another bout of mental illness. Her second daughter accompanied her for treatment at the Guangxi Hospital Of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

(24) 1970 – Moved outside the Guangxi Agricultural College to manage her mental health, later returning to the college after 1982.

(25) Over the next decade after 1970, Su Mei was repeatedly hospitalized in Nanning due to psychiatric relapses.

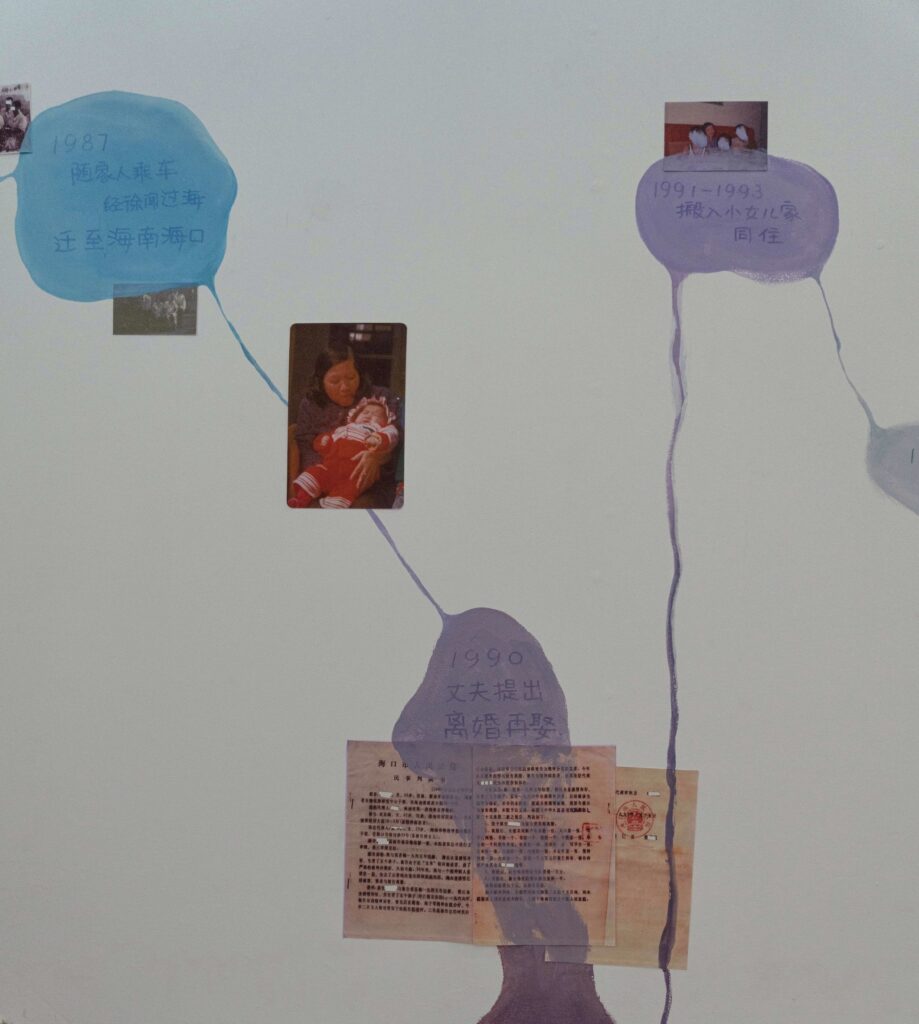

(26) 1987 – Moved to Hainan, crossing from Nanning through Xuwen Port in Guangdong Province on a large truck with the family’s belongings to live in a detached courtyard within the provincial government compound in Haikou.

(27) 1990 – Husband filed for divorce and remarriage. Court granted the divorce.

(28) 1990 – Hospitalized for treatment at Anning Hospital(Psychiatric Hospital) in Haikou, Hainan (medication and electroconvulsive therapy).

(29) 1991-1993 – Moved in with her youngest daughter, residing in the dormitory building of the Hainan Provincial Department of Science and Technology.

(30) 1990 – Su Mei was relocated to a residential area in the government compound in Haikou, Hainan. She frequently wandered away but was brought back home by her children.

(31) 2006 – Fell and fractured her pelvis, leading to exacerbated health issues, inability to move, and reliance on others for care. Her eldest daughter stayed with her, but she refused food and required intravenous nutrition in the hospital.

(32) January 13, 2010 – Su Mei suddenly said, “I am going up to sky ,” instructing her daughter to inform her ex-husband (daughter did not relay the message).

(33) January 14, 2010 – Su Mei passed away at the age of 82, shedding a tear as she took her last breath.

This project (Inner Symbol) is an objectification of self-exploration into mood swings during self-quarantine, with reflection particularly on women’s social status, as well as dynamics between social norms and the physiological instinct as women. Not only a product of self-reflexivity and self-inquiry, this is also an examination into the predicament of women.

This project aims at attracting more social attention on feminist arts within East Asian context. Meanwhile, self-caring and positive attitudes are encouraged through this project among more women, especially girls undergoing the phase of value formation, in the face of gender conundrum.

这一个人项目创作于自我隔离期间,摸索自己的情绪波动及流向,以及将它视觉化的结果,在创作过程使我不断反思自己,尤其是作为女性的社会处境,以及作为女性所接受的身份教育以及身体本能之间的关系。它既是我对自己的不断自省和溯源,也是我对女性身份困境的追问。

借此作品,我希望能东亚社会语境下,引起更多观者对女性主义作品的关注,也希望能让更多的女性,尤其是仍在思维形成阶段的女孩子,更多的关注自身,积极地面对自己的性别困境。

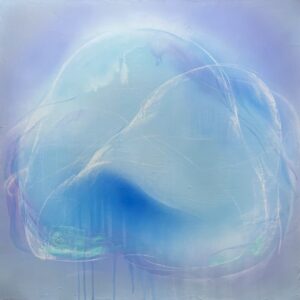

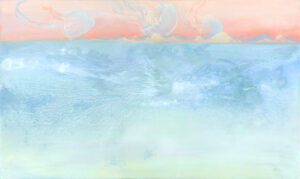

By Awareness with the series of works centered on bodily perceptions, I aim to sculpt and depict abstract expressions of bodily experiences and inner perceptions. This process involves transitioning from conversing with the world to engaging in introspective dialogue, shifting the focus from external to internal scrutiny of my own body and emotions. Through the most direct documentation of my personal experiences and bodily sensations, I seek to externalize my emotions and feelings, transforming the most intimate aspects of “self” into a public, universal narrative. While painting serves as my tool, it is the internal experiences that act as my creative medium. In the process of creation, all contemplations and tangled imageries metamorphose into rhythms, ultimately transforming into visual images.

身体感知系列作品是我塑造刻画到对身体经验、内在感知的抽象表达,这一过程中我从与世界的交谈退回到与自我对话,是对外部世界的移情到对自身身体和情绪审视的转变。我希望通过对我自身私人经验、身体感知体验的最直接的记录,将我的情绪和感受外化,将“我”最私域的东西转变成一种公开的、通用的讲述。绘画是我的手段但内在体验才是我的创作媒介。在创作过程中一切思考和混乱的意象都化为韵律,最后转化成视觉图像。

This series embodies a tangible endeavor of abstract expression representing my personal aesthetics and inner perceptions. Within these everyday emotional fragments and introspective dialogues, I seek to extract a visual symbol originating from within myself, reinterpreting it on canvas through the fusion of color and light.

微光系列是我对自己审美与内在感知抽象表达的具体化尝试,我尝试在这些日常的情绪碎片和于自身的交流中,提取一个视觉符号,它从我的身体中来,通过颜色和光的组合重新在画布上。

During the creative process, I spend extended periods waiting for the entrance of my emotions. When the entrance appears, I delve into the depths of my subconscious, while my self emerges to observe this abyss and record fleeting imageries. Capturing these imageries requires swiftly transforming the fragmented memories of these imageries into visual forms. It is a moment of instantaneous decision-making where victory or defeat hinges on swift action. If the opportunity passes, I regress into a numb state of suppressed subconsciousness, reverting back to the preparatory phase of squatting, a routine devoid of expressive desires and quite disheartening. In my art-making, I strive to eliminate any possibility of nitpicking, returning painting to the most direct process of reaction-observation-action. Through this process, I unlock myself, break free from constraints, and rediscover the most authentic essence of myself in that fleeting moment.

在创作时,我长时间地蹲守等待自己情绪的入口,当入口出现时,我进入潜意识的深渊,而自我则爬出来观察这个深渊并记录瞬时的意象,而捕捉这个意象需要很快速地将这个意象的记忆碎片转化成图像的形态。这是一个瞬间决定胜负的时刻,若时机一过,我退回到潜意识被压抑的麻木状态,也就退回到蹲守的准备阶段,一种没有表达欲望的令人沮丧的日常状态。在绘制中我试图排除任何咬文嚼字的可能,将绘画回归到最直接的反应–观察–行动的过程上,通过这个过程我打开了自我,摆脱框架,找回那一刻最真实的本我。

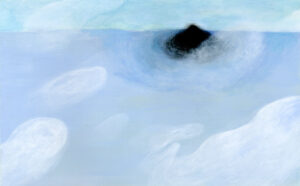

Describing landscapes is my attempt to transpose my inner experiences onto the real world. During this time, I have painted numerous mountains and seas, with a particular fondness for the imagery of islands. The works from this series have subsequently been featured in the cover designs of books centered around island themes.

对风景的描绘是我将自身感受移情到现实世界的尝试,在这个期间,我画了很多的山和海,对岛屿这个意象有很多偏爱,这个系列的作品之后也被用于海岛主题写作的书籍装帧上。